The Enuma Elish (Babylonian Epic – When On High) is a Babylonian or Mesopotamian myth of creation recounting the struggle between cosmic order and chaos. It is basically a myth of the cycle of seasons. It is named after its opening words and was recited on the fourth day of the ancient Babylonian New Year's festival. The basic story exists in various forms in the area. This version is written in Akkadian, an old Babylonian dialect, and stars Marduk, the patron deity of the city of Babylon. A similar earlier version in ancient Sumerian has Anu, Enil and Ninurta as the heroes, suggesting that this version was adapted to justify the religious practices in the cult of Marduk in Babylon.

The Enuma Elish (Babylonian Epic – When On High) is a Babylonian or Mesopotamian myth of creation recounting the struggle between cosmic order and chaos. It is basically a myth of the cycle of seasons. It is named after its opening words and was recited on the fourth day of the ancient Babylonian New Year's festival. The basic story exists in various forms in the area. This version is written in Akkadian, an old Babylonian dialect, and stars Marduk, the patron deity of the city of Babylon. A similar earlier version in ancient Sumerian has Anu, Enil and Ninurta as the heroes, suggesting that this version was adapted to justify the religious practices in the cult of Marduk in Babylon.

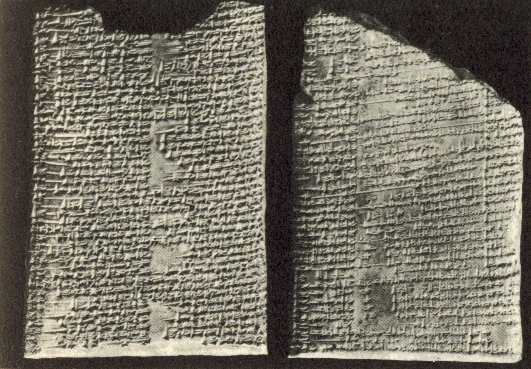

This version was written sometime in the 12th century BC in cuneiform on seven clay tablets. They were found in the middle 19th century in the ruins of the palace of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh. George Smith first published these texts in 1876 as The Chaldean Genesis. Because of many parallels with the Genesis account, some historians concluded that the Genesis account was simply a rewriting of the Babylonian story. As a reaction, many who wanted to maintain the uniqueness of the Bible argued either that there were no real parallels between the accounts or that the Genesis narratives were written first and the Babylonian myth borrowed from the biblical account. Also See >>> The Epic of Gilgamesh Flood and the Bible

However, there are simply too many similarities between the accounts to deny any relationship between the accounts. There are significant differences as well that should not be ignored. Yet there is little doubt that the Sumerian versions of the story predate the biblical account by several hundred years. Rather than opting for either extreme of complete dependence or no contact whatever, it is best to see the Genesis narratives as freely using the metaphors and symbolism drawn from a common cultural pool to assert their own theology about God (see Speaking the Language of Canaan).

The version presented here is a combination of several translations but is substantially based on the translation of E. A. Speiser in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3rd edition, edited by James Pritchard (Princeton, 1969), with modifications based on various other translations (for example, the translation of L.W. King, The Seven Tablets of Creation, London 1902). The translation of these texts is not exact. In some cases, badly damaged tablets make reading the text difficult. Some translators leave the gaps, while others attempt to reconstruct the text based on what remains. In other cases, there are differing interpretations of the meaning of words or the reading of the cuneiform itself. Many translations of the tablets try to capture the sense of the text rather than a literal translation. That is the approach taken here. In this version, many of the names of the gods are left untranslated.

Founder of Lazarus Enterprises Group and head of strategy at Apex Media 365, also Apex Marketing Pro, a leading digital marketing firm.

We developed a system to help small businesses, and local companies connect with potential clients, and customers who truly need their goods or services, which will in-turn increase the company’s net worth with a lot more ease, and control.

We do this utilizing Gorilla marketing tactics, and technology to measure a return on investment.

To schedule a free 30-minute Marketing Tune-up, call us: 1-888-256-4202